THE SEAWEED SOURCE

The blog from which everything seaweed arises

Dulse vs. nori butter

We recently had a chance to try out some seaweed butter recipes.

Typically seaweed butter recipes call for dried nori, which is expected due to the availability of dried nori in most grocery stores. We wanted to try using fresh seaweeds, nori and dulse. After nori and dulse butters were made, we used them on a variety of simple dishes to compare flavors.

Directions to make seaweed butter using fresh seaweeds.

Grab a large handful of fresh nori or dulse (~2-3 oz).

Add seaweed to a food processor with a little water and puree.

Strain pureed seaweed through a coffee filter to remove excess water.

Heat a skillet to medium-low and melt a half stick of non-salted butter (4 Tbs).

Mix in strained pureed seaweed.

Transfer mixture to a dish, cover, and refrigerate.

The seaweed butter can stay in refrigerator for up to two weeks and can now be used at any time in place of regular butter.

Now for the fun part. We used the nori and dulse butter on a a few simple dishes to assess the flavor enhancement and differences. We tried both butters on fried eggs, sauteed zucchini, sauteed mushrooms, bread, mixed veggies, and asparagus.

Dulse Butter: Dulse kept its red color when used to saute vegetables. It gave a much more umami meaty flavor to dishes compared to nori. This is to be expected as dulse contains more glutamic acid which is responsible for umami flavor. Dishes that used dulse had little to no ocean flavor. Dulse butter would be good for any dish where a more savory flavor is wanted.

Nori Butter: Nori butter became dark green when sauteed. Dishes cooked with nori had more ocean flavor than dulse, likely because nori has a higher concentration of lipids. Longer chain fatty acids, like fish oils, give a stronger ocean flavor and are good for human health. Nori butter would better complement seafood dishes like crab, oysters, and fish.

Overall the seaweed butters were well received, even by people that don’t particularity enjoy seafood. The crowd favorite was umami mushrooms, white mushrooms sauteed in dulse butter. These were very simple dishes so the differences in the butters could be detected, that being said, adding new elements such as garlic and lemon would be great things to try.

Dulse

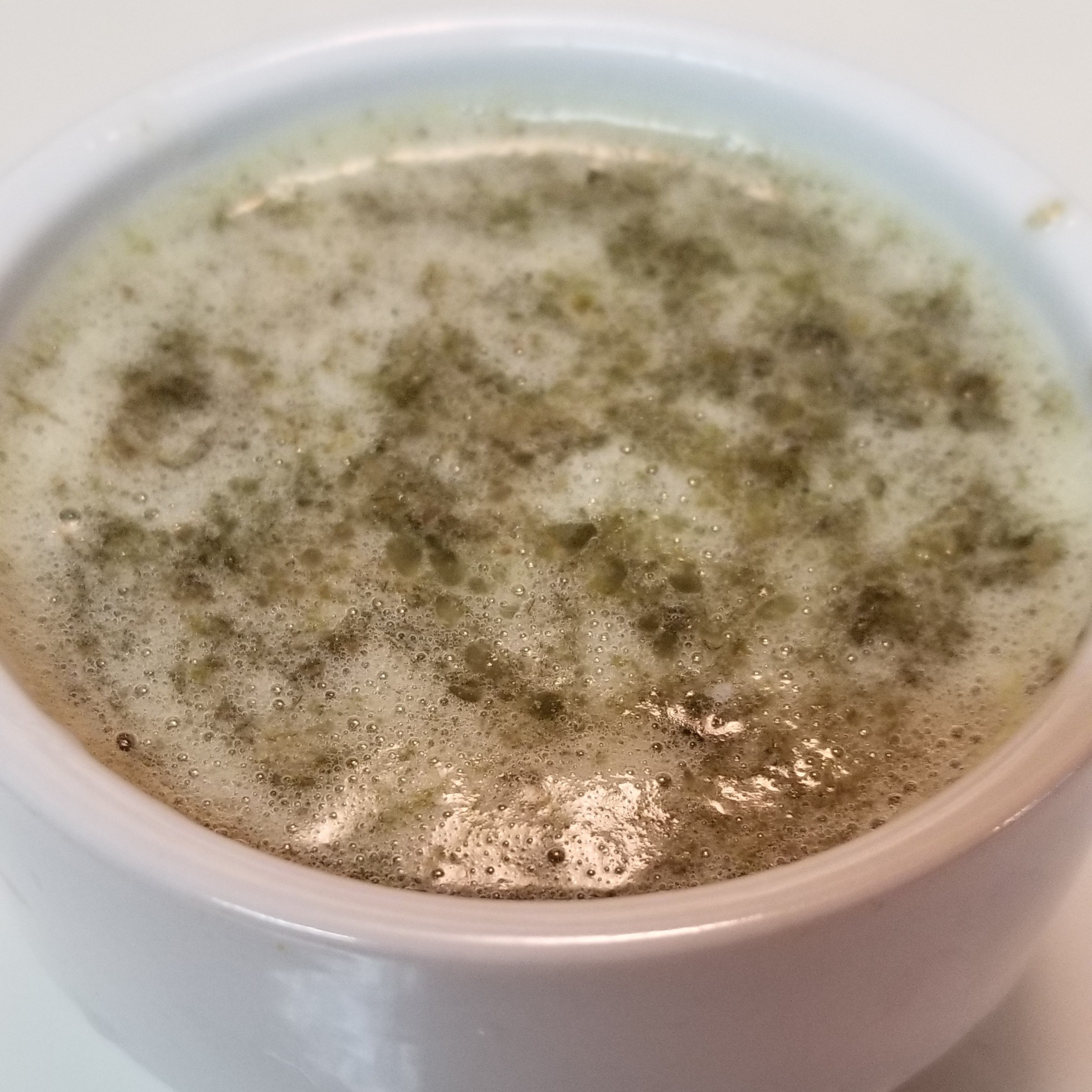

Pureed nori in melted butter

Umami mushrooms sauteed in dulse butter

Nori butter in dish

Sauteed zuchini with dulse butter.

The man who discovered umami

Did you know we owe seaweed for helping discover umami?

Kikunae Ikeda a Japanese chemist and professor at Tokyo Imperial University had been studying a broth made from seaweed and dried fish flakes called dashi. Through numerous chemical assays, Ikeda had been trying to isolate the molecules behind its distinctive taste. In a 1909 paper, Ikeda claimed the flavor in question came from the amino acid glutamate, a building block of proteins. He suggested that the savory sensation triggered by glutamate should be one of the basic tastes that give something flavor, on a par with sweet, sour, bitter, and salt. He called it “umami”, riffing on a Japanese word meaning “delicious”.

Ikeda’s paper was not well received, and it took over a hundred years for the term “umami” to be internationally recognized. Over the decades, scientists began to put together how umami works. Each new insight brought the claim put forth by Ikeda into better focus. The discovery that made umami stick was about 20 years ago, showing that there are specific receptors in taste buds that pick up on amino acids. Multiple research groups have now reported on these receptors, which are tuned to specifically stick onto glutamate.

Ikeda, found a seasoning manufacturer and started to produce his own line of umami seasoning. The product, a monosodium glutamate (MSG) powder called Aji-No-Moto, is still made today. (Although rumors have swirled periodically that eating too much MSG can give people headaches and other health problems, the US Food and Drug Administration has found no evidence for such claims. It just makes food taste more savory.)

While other food items have umami flavors, it was seaweed that gave the term life.

Umami- What it is and how you get it from seaweed

You may have come across the word umami, it’s commonplace in Japanese restaurants and on packaged foods such as ramen or seaweed. Umami can be described as a pleasant "brothy" or "meaty" taste with a long-lasting, mouthwatering and coating sensation over the tongue.

Umami, is a loan word from the Japanese (うま味), umami can be translated as "pleasant savory taste." The word was first proposed in 1908 by Kikunae Ikeda. It wasn’t until 1985 the term was recognized as a scientific term to describe the taste of glutamates and nucleotides at the first Umami International Symposium in Hawaii. This symposium is still active today.

The English synonym would be Savory

Seaweeds are known to produce Umami flavor and are commonly used to make broths. A recent article published in the Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization outlined ideal flavor extraction process for Laminaria japonica, and showed all the flavor components. Below is a breakdown of the chemical constituents of the Umami taste in Laminaria japonica.

“Electronic tongue and electronic nose were used to assess the taste and flavor of the hydrolysate, respectively. Hexanal (43.31 ± 0.57%), (E)-2-octenal (10.42 ± 0.34%), nonanal (6.91 ± 0.65%), pentanal (6.41 ± 0.97%), heptanal (4.64 ± 0.26) and 4-ethylcyclohexanol (4.52 ± 0.21%) were the most abundant flavor compounds in the enzymatic hydrolysate with % peak areas in GC–MS. The contents of aspartic acid (11.27 ± 1.12%) and glutamic acid (13.79 ± 0.21%) were higher than other free amino acids in the enzymatic hydrolysate. Electronic tongue revealed a taste profile characterized by high scores on umami and saltiness .”

All posts are approved by Dr. Michael H. Graham: owner of Monterey Bay Seaweeds and professor of phycology at Moss Landing Marine Labs

Recent posts

-

December 2020

- Dec 28, 2020 Homemade dulse-popcorn recipe Dec 28, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 17, 2020 Watch the first California Seaweed Festival now! (Nov. 16-21, 2020) Nov 17, 2020

- Nov 13, 2020 Seaweeds could, and should, be the future of fuel Nov 13, 2020

- Nov 3, 2020 Prepare for your spring garden by adding seaweed now Nov 3, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 28, 2020 Chef Jacob Harth demonstrates how to harvest and cook seaweeds right at the beach! Oct 28, 2020

-

September 2019

- Sep 23, 2019 Don't be surprised to see more seaweed flavored snacks soon Sep 23, 2019

- Sep 16, 2019 The Dutch Weed Burger! Sep 16, 2019

-

July 2019

- Jul 30, 2019 Innovator makes entire house out of Sargassum bricks Jul 30, 2019

- Jul 23, 2019 New study shows promise that Sargassum sp. improves blood biochemistry profiles Jul 23, 2019

- Jul 17, 2019 How to make your own roasted seaweed snacks. Jul 17, 2019

- Jul 11, 2019 Why do cooked seaweeds turn green? Jul 11, 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Artisan salt makers use seaweed in Japan. Jul 1, 2019

-

June 2019

- Jun 27, 2019 Animals fed an algae rich diet produced more nutritious milk. Jun 27, 2019

- Jun 24, 2019 Dulse vs. nori butter Jun 24, 2019

- Jun 17, 2019 Kampachi Farms LLC sets out to attain off shore permits for offshore seaweed Jun 17, 2019

- Jun 11, 2019 Seaweeds are one of the best things to eat to help preserve biodiversity and the planet Jun 11, 2019

- Jun 3, 2019 seaweeds to combat hypertension Jun 3, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 29, 2019 CHALLENGES FOR SUSTAINABLE SEAWEED AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT IN EUROPE May 29, 2019

- May 24, 2019 Fucoidan used in diet therapy for the prevention and treatment of diabetes mellitus May 24, 2019

- May 21, 2019 TNC and Encourage Capital report on blue revolution investment May 21, 2019

- May 20, 2019 Sodium alginate from Sargassum sp. used as fruit preservation coating May 20, 2019

- May 17, 2019 The race to the methane-free cash cow May 17, 2019

- May 16, 2019 seaweed pasta sauce May 16, 2019

- May 15, 2019 Seaweed cookies May 15, 2019

- May 13, 2019 What will Mexico do with all that sargassum? May 13, 2019

- May 9, 2019 The man who discovered umami May 9, 2019

- May 2, 2019 why seaweed hasn't replaced kale yet May 2, 2019

- May 1, 2019 Roast Chicken With Crunchy Seaweed and Potatoes May 1, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 30, 2019 Nori and kelp butter recipes Apr 30, 2019

- Apr 29, 2019 Seaweed sport drink pouches used at the London Marathon Apr 29, 2019

- Apr 26, 2019 soy sauce made from fermented seaweed instead of soy Apr 26, 2019

- Apr 22, 2019 French chef leads a cooking class focused on seaweed. Apr 22, 2019

- Apr 19, 2019 Apr 19, 2019

- Apr 18, 2019 Marvel's Eat the Universe: aquatic-themed sandwich with fresh seaweed Apr 18, 2019

- Apr 17, 2019 Ramen with kelp stock! Apr 17, 2019

- Apr 16, 2019 Portland chef says, "Throw some seaweed in that!" Apr 16, 2019

- Apr 15, 2019 Seaweed inspired organic sunscreen Apr 15, 2019

- Apr 12, 2019 Operation Crayweed: restoring Sydney's underwater forests. Apr 12, 2019

- Apr 10, 2019 Seaweed in your garden: a good fertilizer and potential pest control Apr 10, 2019

- Apr 9, 2019 New review published on bioactive metabolites within seaweeds Apr 9, 2019

- Apr 8, 2019 New study examines the lipid profile of the sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) Apr 8, 2019

- Apr 5, 2019 Scientists sequence the genome of popular Japanese seaweed (Cladosiphon okamuranus) in preparation for climate change Apr 5, 2019

- Apr 3, 2019 Using macroalgae as an indicator of ocean conditions through time. Apr 3, 2019

- Apr 2, 2019 Flexible Conductors from Brown Algae for Green Electronics Apr 2, 2019

- Apr 1, 2019 "I want kelp on every table in America" Apr 1, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 27, 2019 Old stories told by a retired priest on how to live off seaweed. Mar 27, 2019

- Mar 26, 2019 Seaweed takes the number one spot on Martha Stewart's top 5 food trends Mar 26, 2019

- Mar 25, 2019 Carrageenan extracted from red seaweeds could be used as an antifungal Mar 25, 2019

- Mar 22, 2019 Novel use of alginate from brown seaweeds transports macrophages into damaged tissues Mar 22, 2019

- Mar 20, 2019 Kelp farming is therapeutic, introducing the Salt Sisters group Mar 20, 2019

- Mar 19, 2019 New report: "Development of Offshore Seaweed Cultivation: food safety, cultivation, ecology and economy" Mar 19, 2019

- Mar 18, 2019 North America's first-ever seaweed-focused restaurant week Mar 18, 2019

- Mar 14, 2019 Seaweed Pie Recipe for Pi Day (3.14) Mar 14, 2019

- Mar 13, 2019 Seaweed Beers are Gaining in Popularity Mar 13, 2019

- Mar 11, 2019 Seaweed Farmers in Japan are Creating new Varieties to Deal with Climate Change. Mar 11, 2019

- Mar 8, 2019 Pickled Kelp Recipe Mar 8, 2019

- Mar 7, 2019 Brown Seaweeds Could be Used to Make Bioethanol Mar 7, 2019

- Mar 6, 2019 NOVAMEAT has Created Artificial Steak using Plants and Algae Mar 6, 2019

- Mar 5, 2019 The Nature Conservancy is Changing its Tune to Seaweed Aquaculture Mar 5, 2019

- Mar 4, 2019 Monterey Bay Seaweeds Featured at F3 Meeting in SF Mar 4, 2019

- Mar 1, 2019 100 year old maps help create historic digital kelp distribution Mar 1, 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 28, 2019 Canadian seaweed infused gin wins award Feb 28, 2019

- Feb 14, 2019 Happy Valentine's Day: Chocolate Truffles with Seaweed Feb 14, 2019

- Feb 12, 2019 Korean style kelp noodles Feb 12, 2019

- Feb 8, 2019 Cargill works to help make larger sustainable red seaweed market. Feb 8, 2019

- Feb 7, 2019 κ-Carrageenan Hydrogel as a Coating Material for Fertilizers Feb 7, 2019

- Feb 6, 2019 Happy seaweed day! Feb 6, 2019

- Feb 5, 2019 New report outlines seaweed market growth and hindrances. Feb 5, 2019

- Feb 4, 2019 Seaweed folklore: Predicting rain Feb 4, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 17, 2019 Umami- What it is and how you get it from seaweed Jan 17, 2019

- Jan 15, 2019 The shellfish industry needs a kelping hand in fighting ocean acidification Jan 15, 2019

- Jan 14, 2019 Blooming 3D-jelly cakes made from seaweed sugars. Jan 14, 2019

- Jan 11, 2019 New artificial shrimp are made from algae Jan 11, 2019

- Jan 10, 2019 Extracting proteins from seaweed just got a little easier. Jan 10, 2019

- Jan 9, 2019 From the makers of the seaweed surfboard, comes Triton flip-flops: sandals made from algae! Jan 9, 2019

- Jan 8, 2019 Shrimp farming is getting a boost from incorporating seaweeds Jan 8, 2019

- Jan 7, 2019 How ocean acidification could restructure natural seaweed communities Jan 7, 2019

- Jan 4, 2019 Sodium alginate and human stem cells used to 3D-print tissues Jan 4, 2019

- Jan 3, 2019 U.S. seaweed consumption is growing about 7% a year Jan 3, 2019

- Jan 2, 2019 Chileans are shifting from seaweed gatherers to cultivators Jan 2, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 28, 2018 New study uses matrix approach to evaluate ecosystem services by seaweeds Dec 28, 2018

- Dec 27, 2018 Carrageenan and silver to combat drug resistant bacteria Dec 27, 2018

- Dec 26, 2018 Chinese new year seaweed snack Dec 26, 2018

- Dec 20, 2018 Real kombucha is made from seaweed Dec 20, 2018

- Dec 19, 2018 Food & Wine predicts seaweed to be one of the biggest food trends of 2019! Dec 19, 2018

- Dec 18, 2018 Looking for an art and craft idea? How about seaweed holiday ornaments? Dec 18, 2018

- Dec 14, 2018 Farm bill passes that dramatically expands federal support for algae agriculture! Dec 14, 2018

- Dec 13, 2018 Climate change is raising iodine levels in seaweed. Cause for alarm? We think not. Dec 13, 2018

- Dec 10, 2018 Tanzania government backs seaweed farming Dec 10, 2018

- Dec 6, 2018 Seaweed common names: Kombu Dec 6, 2018

- Dec 5, 2018 MOROCCAN LAMB STEW WITH DULSE Dec 5, 2018

- Dec 4, 2018 Kampachi farms was awarded a $3.3 million grant to study seaweed as a source of energy and food Dec 4, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 30, 2018 Seaweed common names: Laver Nov 30, 2018

- Nov 28, 2018 Seaweed smart material stronger than steel Nov 28, 2018

- Nov 27, 2018 Seaweed common names: Wakame Nov 27, 2018

- Nov 26, 2018 Seaweed common names: Nori Nov 26, 2018

- Nov 21, 2018 A seaweed thanksgiving: Gravy Nov 21, 2018

- Nov 19, 2018 A seaweed thanksgiving: seaweed steak sauce Nov 19, 2018

- Nov 16, 2018 Whole Foods predicts uptick in seaweed snacks in 2019. Nov 16, 2018

- Nov 15, 2018 A seaweed thanksgiving Nov 15, 2018

- Nov 13, 2018 A seaweed Thanksgiving: fried yams with dulse Nov 13, 2018

- Nov 12, 2018 The origin of the word Kelp, and how it helped win the first world war Nov 12, 2018

- Nov 9, 2018 A seaweed thanksgiving part 1: mashed potatoes Nov 9, 2018

- Nov 8, 2018 Seaweed extracts used to make clothing Nov 8, 2018

- Nov 6, 2018 Stressed out? Take a relaxing seaweed bath. Nov 6, 2018

- Nov 5, 2018 offshore vs. land-based seaweed farms, and why we went land. Nov 5, 2018

- Nov 2, 2018 Closing the nutrient loop with seaweed farming. Nov 2, 2018

- Nov 1, 2018 Seaweeds can facilitate symbiotic microbes in agriculture Nov 1, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 30, 2018 How do farmers get giant pumpkins? With a little help from seaweed. Oct 30, 2018

- Oct 29, 2018 Seaweed Pasta Oct 29, 2018

- Oct 27, 2018 Moss Landing Marine Labs gets funding to study macroalgae in livestock feed Oct 27, 2018

- Oct 25, 2018 Robots are coming to save kelp forests from urchins Oct 25, 2018

- Oct 24, 2018 India approves 1 billion USD in aquaculture infrastructure development Oct 24, 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Eating brown seaweed can aid in weight loss Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 22, 2018 Seaweed and cow gas Oct 22, 2018

- Oct 19, 2018 Concerned about plastic pollution? Seaweed can help. Oct 19, 2018

- Oct 18, 2018 It's national seafood month. Let's not forget seaweed. Oct 18, 2018

- Oct 17, 2018 What the heck is seaweed anyway? Oct 17, 2018

- Oct 15, 2018 Could you survive by only eating seaweed? Oct 15, 2018

- Oct 13, 2018 Replace your daily fish oil supplement with algae. Oct 13, 2018

- Oct 12, 2018 Which seaweeds are toxic? Oct 12, 2018

- Oct 11, 2018 Can seaweed combat climate change? Oct 11, 2018

- Oct 9, 2018 Is seaweed the new superfood? Oct 9, 2018

- Oct 8, 2018 The Russians are investing in aquaculture while the USA is standing by Oct 8, 2018

- Oct 7, 2018 Of Carrageenan and Health Oct 7, 2018

- Oct 4, 2018 Our dulse is being served in the #1 restaurant in the world- Eleven Madison Park. Oct 4, 2018

- Oct 3, 2018 What makes the red abalone red? Oct 3, 2018

- Oct 2, 2018 Do you have a question about seaweed, do you ask a phycologist or an algologist? Oct 2, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 AlgaeBase: One of the best algae resources available! Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 27, 2018 How will we feed 9.6 billion people in 2050? The solution is within the ocean Sep 27, 2018

- Sep 26, 2018 Otters and urchins and kelp ... oh my! Does your kelp forest require otters? Maybe not. Sep 26, 2018

- Sep 19, 2018 Hello World! Sep 19, 2018

Posts by Categories